A curious tale¶

Here is a story where we develop a very simple system for storing file snapshots. We soon find it starts to look just like git.

The end of the story¶

To understand why git does what it does, we first need to think about what a content manager should do, and why we would want one.

If you’ve read the git parable (please do), then you’ll recognize many of the ideas. Why? Because they are good ideas, worthy of re-use.

As in the git parable, we will try and design our own content manager, and then see what git has to say.

(If you don’t mind reading some Python code, and more jokes, then also try my git foundation page).

While we are designing our own content management system, we will do a lot of stuff longhand, to show how things work. When we get to git, we will find it does these tasks for us.

The story begins¶

You are writing a breakthrough paper showing that you can explain how the

brain works by careful processing of some interesting data. You’ve got the

analysis script, the data file and a figure for the paper. These are all in a

directory modestly named nobel_prize.

You can get this, the first draft, by downloading and unzipping

nobel_prize.

Here’s the current contents of our nobel_prize directory:

nobel_prize

├── clever_analysis.py [618B]

├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

└── fancy_figure.png [183K]

The dog ate my results¶

You’ve been working on this study for a while.

At first, you were very excited with the results. You ran the script, made the

figure, and the figure looked good. That’s the figure you currently have in

nobel_prize directory. You took this figure to your advisor, Josephine.

She was excited too. You get ready to publish in Science.

You’ve done a few changes to the script and figure since then. Today you finished cleaning up for the Science paper, and reran the analysis, and it doesn’t look quite the same. You go to see Josephine. She says “It used to look better than that”. That’s what you think too. But:

Did it really look different before?

If it did, what caused the change in the figure?

Deja vu all over again¶

Given you are so clever and you have discovered how the brain works, it is really easy for you to leap in your time machine, and go back two weeks to start again.

What are you going to do differently this time?

Gitwards 1: make regular snapshots¶

You decide to make your own content management system. It’s the simplest thing that could possibly work, so you call it the “Simple As Possible” system, or SAP for short.

Every time you finish doing some work on your paper, you make a snapshot of all the files for the paper.

The snapshot is a copy of all the files in the working directory.

First you make a directory called working, and move your files to that

directory:

nobel_prize

└── working

├── clever_analysis.py [618B]

├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

└── fancy_figure.png [183K]

When you’ve finished work for the day, you make a snapshot of the directory containing the files you are working on. The snapshot is just a copy of your working directory:

nobel_prize

├── working

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [618B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ └── fancy_figure.png [183K]

└── snapshot_1

├── clever_analysis.py [618B]

├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

└── fancy_figure.png [183K]

You are going to do this every day you work on the project.

On the second day, you add your first draft of the paper, nobel_prize.md.

You can download this ground-breaking work at nobel_prize.md.

nobel_prize

├── working

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [618B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [183K]

│ └── nobel_prize.md [730B]

└── snapshot_1

├── clever_analysis.py [618B]

├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

└── fancy_figure.png [183K]

At the end of the day you make your second snapshot:

nobel_prize

├── working

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [618B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [183K]

│ └── nobel_prize.md [730B]

├── snapshot_2

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [618B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [183K]

│ └── nobel_prize.md [730B]

└── snapshot_1

├── clever_analysis.py [618B]

├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

└── fancy_figure.png [183K]

On the third day, you did some edits to the analysis script, and refreshed the figure by running the script. You did a third snapshot.

nobel_prize

├── working

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [716B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [239K]

│ └── nobel_prize.md [730B]

├── snapshot_3

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [716B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [239K]

│ └── nobel_prize.md [730B]

├── snapshot_2

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [618B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [183K]

│ └── nobel_prize.md [730B]

└── snapshot_1

├── clever_analysis.py [618B]

├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

└── fancy_figure.png [183K]

To make the directory listing more compact, I’ll sometimes show only the number of files / directories in a subdirectory. For example, here’s a listing of the three snapshots, but only showing the contents of the third snapshot:

nobel_prize

├── working

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [716B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [239K]

│ └── nobel_prize.md [730B]

├── snapshot_3

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [716B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [239K]

│ └── nobel_prize.md [730B]

├── snapshot_2

│ (4 files)

└── snapshot_1

(3 files)

Finally, on the fourth day, you make some more edits to the script, and you add some references for the paper.

nobel_prize

├── working

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [752B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [251K]

│ ├── nobel_prize.md [730B]

│ └── references.bib [244B]

├── snapshot_4

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [752B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [251K]

│ ├── nobel_prize.md [730B]

│ └── references.bib [244B]

├── snapshot_3

│ (4 files)

├── snapshot_2

│ (4 files)

└── snapshot_1

(3 files)

You are ready for your fateful meeting with Josephine. Again she notices that

the figure is different from the first time you showed her. This time you can

go and look in nobel_prize/snapshot_1 to see if the figure really is

different. Then you can go through the snapshots to see where the figure

changed.

You’ve already got a useful content management system, but you are going to make it better.

Note

We are already at the stage where we can define some terms that apply to our system and that will later apply to git:

- Commit

A completed snapshot. For example,

snapshot_1contains one commit.- Working tree

The files you are working on in

nobel_prize/working.

Gitwards 2: reminding yourself of what you did¶

Your experience tracking down the change in the figure makes you think that it would be good to save a message with each snapshot (commit) to record the commit date and some text giving a summary of the changes you made. Next time you need to track down when and why something changed, you can look at the message to give yourself an idea of the changes in the commit. That might save you time when you want to narrow down where to look for problems.

So, for each commit, you write write a file called message.txt. The

message for the first commit looks like this:

snapshot_1/message.txtDate: April 1 2012, 14.30

Author: I. M. Awesome

Notes: First backup of my amazing idea

There is a similar messsage.txt file for each commit. For example,

here’s the message for the third commit:

snapshot_3/message.txtDate: April 3 2012, 11.20

Author: I. M. Awesome

Notes: Add another fudge factor

This third message is useful because it gives you a hint that this was where you made the important change to the script and figure.

Note

- Commit message

Information about a commit, including the author, date, time, and some information about the changes in the commit, compared to the previous commits.

Gitwards 3: breaking up work into chunks¶

Now you are used to your new system, you find that you like to break your changes up into self-contained chunks of work, each with their own commit, and a matching commit message. When you look back at your fourth commit, it looks like you included two separate chunks of work into the same commit. You’ve even confessed to this in your commit message:

snapshot_4/message.txtDate: April 4 2012, 01.40

Author: I. M. Awesome

Notes: Change analysis and add references

You realize that you will often be in the situation where you have made several changes in the working tree, and you want to split those changes up into different commits, with their own commit messages. How can you adapt SAP to deal with that situation?

To help yourself think about this problem, you decide to scrap your last

commit, and go back to the situation where your working tree has the changes,

but the snapshots (commits) do not. All you have to do to get there, is

delete the snapshot_4 directory:

nobel_prize

├── working

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [752B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [251K]

│ ├── nobel_prize.md [730B]

│ └── references.bib [244B]

├── snapshot_3

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [716B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [239K]

│ ├── nobel_prize.md [730B]

│ └── message.txt [80B]

...

You still have your changes in the working tree. You have changed the

analysis script and figure, and you have the new references.bib file.

You want to break these changes up into two separate commits:

a commit with the changes to the analysis script and figure, but without the references;

another commit to add the references.

To do this kind of thing, you are going to use a new directory called

staging. The staging directory starts off with the files from the

last commit. When you want to add some changes that will go into your next

commit, you copy the changes from the working tree to the staging

directory. You make the commit by copying the contents of staging to a

new snapshot directory, and adding a commit message.

To get started, you make the new staging directory by copying the contents

of the last commit (except the commit message):

nobel_prize

├── working

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [752B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [251K]

│ ├── nobel_prize.md [730B]

│ └── references.bib [244B]

├── staging

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [716B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [239K]

│ └── nobel_prize.md [730B]

├── snapshot_3

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [716B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [239K]

│ ├── nobel_prize.md [730B]

│ └── message.txt [80B]

...

Call the staging directory – the staging area. Your new sequence

for making a commit is:

copy any changes for the next commit from the working tree to the staging area;

make the commit by copying the contents of the staging area to a snapshot directory, and adding a commit message.

You are doing this by hand, but later git will make this much more automatic.

Now you are ready to make the first of your two new commits. You copy the changed analysis script and figure from the working tree to the staging area:

$ cp working/clever_analysis.py staging

$ cp working/fancy_figure.png staging

The staging directory (staging area) now contains the right files for the first of your two commits.

Next you make a commit by copying the staging area to snapshot_4 and

adding a message:

snapshot_4/message.txtDate: April 4 2012, 01.40

Author: I. M. Awesome

Notes: Change parameters of analysis

This gives:

nobel_prize

├── working

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [752B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [251K]

│ ├── nobel_prize.md [730B]

│ └── references.bib [244B]

├── staging

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [752B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [251K]

│ └── nobel_prize.md [730B]

├── snapshot_4

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [752B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [251K]

│ ├── nobel_prize.md [730B]

│ └── message.txt [85B]

...

To finish, you make the second of the two commits. Remember the sequence:

copy any changes for the next commit from the working tree to the staging area;

make the commit by taking a snapshot of the staging area.

You copy the rest of the changes to the staging area:

$ cp working/references.bib staging

Finally, you do the commit by copying the contents of staging to a new

directory snapshot_5, and adding a commit message:

snapshot_5/message.txtDate: April 4 2012, 02.10

Author: I. M. Awesome

Notes: Add references

Now you have:

nobel_prize

├── working

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [752B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [251K]

│ ├── nobel_prize.md [730B]

│ └── references.bib [244B]

├── staging

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [752B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [251K]

│ ├── nobel_prize.md [730B]

│ └── references.bib [244B]

├── snapshot_5

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [752B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [251K]

│ ├── nobel_prize.md [730B]

│ ├── references.bib [244B]

│ └── message.txt [70B]

...

We can add a couple of new terms to our vocabulary:

Note

- Staging area

Temporary area that contains the contents of the next commit. We copy changes from the working tree to the staging area to stage those changes. We make the new commit from the contents of the staging area.

Gitwards 4: getting files from previous commits¶

Remember that you found the figure had changed?

You also found that the problem was in the third commit.

Now you look back over the commits, you realize that your first draft of the analysis script was correct, and you decide to restore that.

To do that, you will checkout the script from the first commit

(snapshot_1). You also want to checkout the generated figure.

Following our new standard staging workflow, that means:

get the files you want from the old commit into the working directory, and the staging area;

make a new commit from the staging area.

For our simple SAP system, that looks like this:

$ # Copy files from old commit to working tree

$ cp snapshot_1/clever_analysis.py working

$ cp snapshot_1/fancy_figure.png working

$ # Copy files from working tree to staging area

$ cp working/clever_analysis.py staging

$ cp working/fancy_figure.png staging

Then do the commit by copying staging, and add a message:

snapshot_6/message.txtDate: April 5 2012, 18.40

Author: I. M. Awesome

Notes: Revert to original script & figure

This gives:

nobel_prize

├── working

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [618B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [183K]

│ ├── nobel_prize.md [730B]

│ └── references.bib [244B]

├── staging

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [618B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [183K]

│ ├── nobel_prize.md [730B]

│ └── references.bib [244B]

├── snapshot_6

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [618B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [183K]

│ ├── nobel_prize.md [730B]

│ ├── references.bib [244B]

│ └── message.txt [90B]

├── snapshot_5

│ (6 files)

├── snapshot_4

│ (5 files)

├── snapshot_3

│ (5 files)

├── snapshot_2

│ (5 files)

└── snapshot_1

├── clever_analysis.py [618B]

├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

├── fancy_figure.png [183K]

└── message.txt [87B]

Note

- Checkout (a file)

To checkout a file is to restore the copy of a file as stored in a particular commit.

Gitwards 5: two people working at the same time¶

One reason that git is so powerful is that it works very well when more than one person is working on the files in parallel.

Josephine is impressed with your SAP content management system, and wants to

use it to make some edits to the paper. She takes a copy of your

nobel_prize directory to put on her laptop.

She goes away for a conference.

While she is away, you do some work on the analysis script, and regenerate the

figure, to make shapshot_7:

nobel_prize

├── working

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [692B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [279K]

│ ├── nobel_prize.md [730B]

│ └── references.bib [244B]

├── staging

│ (5 files)

├── snapshot_7

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [692B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [279K]

│ ├── nobel_prize.md [730B]

│ ├── references.bib [244B]

│ └── message.txt [75B]

...

Meanwhile, Josephine decides to work on the paper. Following your procedure, she makes a commit herself.

What should Josephine’s commit directory be called?

She could call it snapshot_7, but then, when she gets back to the lab, and

gives you her nobel_prize directory, her copy of nobel_prize and yours

will both have a snapshot_7 directory, but they will be different. It

would be easy to copy Josephine’s directory over yours or yours over

Josephine’s, and lose the work.

For the moment, you decide that Josephine will attach her name to the commit

directory, to make it clear this is her snapshot. So, she makes her commit

into the directory snapshot_7_josephine. When she comes back from the

conference, you copy her snapshot_7_josephine into your nobel_prize

directory:

nobel_prize

├── working

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [692B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [279K]

│ ├── nobel_prize.md [730B]

│ └── references.bib [244B]

├── staging

│ (5 files)

├── snapshot_7

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [692B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [279K]

│ ├── nobel_prize.md [730B]

│ ├── references.bib [244B]

│ └── message.txt [75B]

├── snapshot_7_josephine

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [618B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [183K]

│ ├── nobel_prize.md [979B]

│ ├── references.bib [244B]

│ └── message.txt [80B]

...

After the copy, you still have your own copy of the working tree, without Josephine’s changes to the paper. You want to combine your changes with her changes. To do this you do a merge by copying her changes to the paper into the working directory.

$ # Get Josephine's changes to the paper

$ cp snapshot_7_josephine/nobel_prize.md working

Now you do a commit with these merged changes, by copying them into the

staging area, and thence to snapshot_8, with a suitable message:

nobel_prize

├── working

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [692B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [279K]

│ ├── nobel_prize.md [979B]

│ └── references.bib [244B]

├── staging

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [692B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [279K]

│ ├── nobel_prize.md [979B]

│ └── references.bib [244B]

├── snapshot_8

│ ├── clever_analysis.py [692B]

│ ├── expensive_data.csv [244K]

│ ├── fancy_figure.png [279K]

│ ├── nobel_prize.md [979B]

│ ├── references.bib [244B]

│ └── message.txt [82B]

...

This new commit is the result of a merge, and therefore it is a merge commit.

Note

- Merge

To make a new merge commit by combining changes from two (or more) commits.

Gitwards 6: how should you name your commit directories?¶

You like your new system, and so does Josephine, but you don’t much like your

solution of adding Josephine’s name to the commit directory – as in

snapshot_7_josephine. There might be lots of people working on this

paper. With your naming system, you have to give out a unique name to each

person working on nobel_prize. As you think about this problem, you begin

to realize that what you want is a system for giving each commit directory a

unique name, that comes from the contents of the commit. This is where you

starting thinking about hashes.

A diversion on cryptographic hashes¶

This section describes “Cryptographic hashes”. These will give us an excellent way to name our snapshots. Later we will see that they are central to the way that git works.

See : Wikipedia on hash functions.

A hash is the result of running a hash function over a block of data. The hash is a fixed length string that is the characteristic fingerprint of that exact block of data. One common hash function is called SHA1. Let’s run this via the command line:

$ # Make a file with a single line of text

$ echo "git is a rude word in UK English" > git_is_rude

$ # Show the SHA1 hash

$ shasum git_is_rude

30ad6c360a692c1fe66335bb00d00e0528346be5 git_is_rude

Not too exciting so far. However, the rather magical nature of this string is not yet apparent. This SHA1 hash is a cryptographic hash because:

the hash value is (almost) unique to this exact file contents, and

it is (almost) impossible to find some other file contents with the same hash.

By “almost impossible” I mean that finding a file with the same hash is roughly the same level of difficulty as trying something like \(16^{40}\) different files (where 16 is the number of different hexadecimal digits, and 40 is the length of the SHA1 string).

In other words, there is no practical way for you to find another file with different contents that will give the same hash.

For example, a tiny change in the string makes the hash completely different. Here I’ve just added a full stop at the end:

$ echo "git is a rude word in UK English." > git_is_rude_stop

$ shasum git_is_rude_stop

23d97b00299c250b43049be67c97cf2e5ffc2428 git_is_rude_stop

So, if you give me some data, and I calculate the SHA1 hash value, and it

comes out as 30ad6c360a692c1fe66335bb00d00e0528346be5, then I can be very

sure that the data you gave me was exactly the ASCII string “git is a rude

word in UK English”.

Gitwards 7: naming commits from hashes¶

Now you have hashing under your belt, maybe it would be a good way of making a

unique name for the commits. You could take the SHA1 hash for the

message.txt for each commit, and use that SHA1 hash as the name for the

commit directory. Because each message has the date and time and author and

notes, it’s very unlikely that any two message.txt files will be the same.

Here are the hashes for the current message.txt files:

$ # Show the SHA1 hash values for each message.txt

$ shasum snapshot*/message.txt

99b52473039acea4427e13e42b96c78776e2baf5 snapshot_1/message.txt

d396475cc691c8ac7ba7a318726f220c924cf60b snapshot_2/message.txt

6a04028960ead9e8db180dd6ebc108e1fc52891d snapshot_3/message.txt

1bae5edb2785ae73353ae8a691cdb45d182db0c6 snapshot_4/message.txt

2bef6ebeef1dee1610f6581e42fa1a74045042c2 snapshot_5/message.txt

5709c1f836244dc039f05e5d3b0c31267ee785c5 snapshot_6/message.txt

62f0c997a4ddbfe07d6d2524d23883a3ac6ac051 snapshot_7/message.txt

4063178db6bf986c679bfc2c4dde01092146d197 snapshot_7_josephine/message.txt

df3e787c2a89ac991b1c89b39fb014c1f049a939 snapshot_8/message.txt

For example you could rename the snapshot_1 directory to 99b52473039acea4427e13e42b96c78776e2baf5,

then rename snapshot_2 to d396475cc691c8ac7ba7a318726f220c924cf60b and so on.

nobel_prize

├── working

│ (5 files)

├── staging

│ (5 files)

├── df3e787c2a89ac991b1c89b39fb014c1f049a939

│ (6 files)

├── 4063178db6bf986c679bfc2c4dde01092146d197

│ (6 files)

├── 62f0c997a4ddbfe07d6d2524d23883a3ac6ac051

│ (6 files)

├── 5709c1f836244dc039f05e5d3b0c31267ee785c5

│ (6 files)

├── 2bef6ebeef1dee1610f6581e42fa1a74045042c2

│ (6 files)

├── 1bae5edb2785ae73353ae8a691cdb45d182db0c6

│ (5 files)

├── 6a04028960ead9e8db180dd6ebc108e1fc52891d

│ (5 files)

├── d396475cc691c8ac7ba7a318726f220c924cf60b

│ (5 files)

└── 99b52473039acea4427e13e42b96c78776e2baf5

(4 files)

The problem you have now is that the directory names no longer tell you the

sequence of the commits, so you can’t tell that snapshot_2 (now

d396475cc691c8ac7ba7a318726f220c924cf60b) follows snapshot_1 (now 99b52473039acea4427e13e42b96c78776e2baf5).

OK – you scratch the renaming for now while you have a rethink.

nobel_prize

├── working

│ (5 files)

├── staging

│ (5 files)

├── snapshot_8

│ (6 files)

├── snapshot_7

│ (6 files)

├── snapshot_7_josephine

│ (6 files)

├── snapshot_6

│ (6 files)

├── snapshot_5

│ (6 files)

├── snapshot_4

│ (5 files)

├── snapshot_3

│ (5 files)

├── snapshot_2

│ (5 files)

└── snapshot_1

(4 files)

You still want to rename the commit directories, from the message.txt

hashes, but you need a way to store the sequence of commits, after you have

done this.

After some thought, you come up with a quite brilliant idea. Each

message.txt will point back to the previous commit in the sequence. You

add a new field to messsage.txt called Parents.

snapshot_1/message.txt stays the same, because it has no parents:

$ cat snapshot_1/message.txt

Date: April 1 2012, 14.30

Author: I. M. Awesome

Notes: First backup of my amazing idea

snapshot_2/message.txt does change, because it now points back to

snapshot_1. But, you’re going to rename the snapshot directories, so you

want snapshot_2/message.txt to point back to the hash for

snapshot_1/message.txt, which you know is 99b52473039acea4427e13e42b96c78776e2baf5:

$ cat snapshot_2/message.txt

Date: April 2 2012, 18.03

Author: I. M. Awesome

Notes: Add first draft of paper

Parents: 99b52473039acea4427e13e42b96c78776e2baf5

Now we’ve changed the contents and therefore the hash for

snapshot_2/message.txt. The hash was d396475cc691c8ac7ba7a318726f220c924cf60b, but now it

is:

$ shasum snapshot_2/message.txt

9bf4cdd8847feeb49fe94cb96298acf7986a587d snapshot_2/message.txt

You keep doing this procedure, for all the commits, modifying message.txt

and recalculating the hash, until you come to snapshot_8, the merge

commit. This commit is the result of merging two commits: snapshot_7 and

snapshot_7_josephine. You can record this information by putting two

parents into the Parents field of snapshot_8/message.txt, being the

new hashes for snapshot_7/message.txt and

snapshot_7_josephine/message.txt:

$ shasum snapshot_7/message.txt

bee09a3b1c11456c6e1bc6784319954f40fef24b snapshot_7/message.txt

$ shasum snapshot_7_josephine/message.txt

905376d349af193c367217712bc231186f17fca7 snapshot_7_josephine/message.txt

$ cat snapshot_8/message.txt

Date: April 7 2012, 15.03

Author: I. M. Awesome

Notes: Merged Josephine's changes

Parents: bee09a3b1c11456c6e1bc6784319954f40fef24b 905376d349af193c367217712bc231186f17fca7

With the new Parents field, you have new hashes for all the

message.txt files, except snapshot_1 (that has no parent):

$ shasum snapshot_*/message.txt

99b52473039acea4427e13e42b96c78776e2baf5 snapshot_1/message.txt

9bf4cdd8847feeb49fe94cb96298acf7986a587d snapshot_2/message.txt

d9accd0a27c78b4333d70ee1a9d7dca0bcc3e682 snapshot_3/message.txt

00d03e9d1bf4ebaea380da3c62e9226189e39ff4 snapshot_4/message.txt

c203516a49d48389826b041f4d7bd2d39bdf4a57 snapshot_5/message.txt

9920fff7b55370a2c4c7566011de8aa2a263171f snapshot_6/message.txt

bee09a3b1c11456c6e1bc6784319954f40fef24b snapshot_7/message.txt

905376d349af193c367217712bc231186f17fca7 snapshot_7_josephine/message.txt

bd9dc5fb9aacf208536fad1fad22696c9a79e277 snapshot_8/message.txt

You can now rename your snapshot directories with the hash values, safe in the

knowledge that the message.txt files have the information about the commit

sequence.

nobel_prize

├── working

│ (5 files)

├── staging

│ (5 files)

├── bd9dc5fb9aacf208536fad1fad22696c9a79e277

│ (6 files)

├── 905376d349af193c367217712bc231186f17fca7

│ (6 files)

├── bee09a3b1c11456c6e1bc6784319954f40fef24b

│ (6 files)

├── 9920fff7b55370a2c4c7566011de8aa2a263171f

│ (6 files)

├── c203516a49d48389826b041f4d7bd2d39bdf4a57

│ (6 files)

├── 00d03e9d1bf4ebaea380da3c62e9226189e39ff4

│ (5 files)

├── d9accd0a27c78b4333d70ee1a9d7dca0bcc3e682

│ (5 files)

├── 9bf4cdd8847feeb49fe94cb96298acf7986a587d

│ (5 files)

└── 99b52473039acea4427e13e42b96c78776e2baf5

(4 files)

Now the commit directories are hash names, it is harder to see which commit is

which, so here’s the directory listing where the commit directories have a

label from the Notes: field in message.txt:

nobel_prize

├── working

│ (5 files)

├── staging

│ (5 files)

├── bd9dc5fb9aacf208536fad1fad22696c9a79e277 "Merged Josephine's changes"

│ (6 files)

├── 905376d349af193c367217712bc231186f17fca7 "Expand the introduction"

│ (6 files)

├── bee09a3b1c11456c6e1bc6784319954f40fef24b "More fun with fudge"

│ (6 files)

├── 9920fff7b55370a2c4c7566011de8aa2a263171f "Revert to original script & figure"

│ (6 files)

├── c203516a49d48389826b041f4d7bd2d39bdf4a57 "Add references"

│ (6 files)

├── 00d03e9d1bf4ebaea380da3c62e9226189e39ff4 "Change parameters of analysis"

│ (5 files)

├── d9accd0a27c78b4333d70ee1a9d7dca0bcc3e682 "Add another fudge factor"

│ (5 files)

├── 9bf4cdd8847feeb49fe94cb96298acf7986a587d "Add first draft of paper"

│ (5 files)

└── 99b52473039acea4427e13e42b96c78776e2baf5 "First backup of my amazing idea"

(4 files)

Note

- Commit hash

The hash value for the file containing the commit message.

Gitwards 8: the development history is a graph¶

The commits are linked by the “Parents” field in the message.txt file. We

can think of the commits in a graph, where the commits are the nodes, and the

links between the nodes come from the hashes in the “Parents” field.

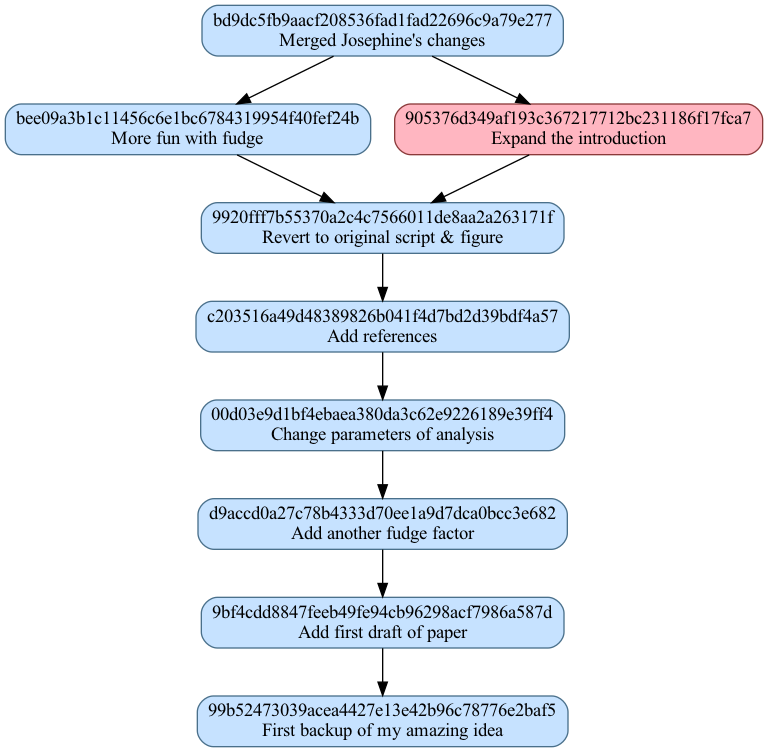

Graph of development history for your SAP content management system. The

most recent commit is at the top, the first commit is at the bottom. Your

commits are in blue, Josephine’s are in pink. Each commit label has the

hash for the commit message, and the note in the message.txt file.¶

Gitwards 9: saving space with file hashes¶

While you’ve been working on your system, you’ve noticed that your snapshots

are not efficient on disk space. For example, every commit / snapshot has an

identical copy of the data expensive_data.csv. If you had bigger files or

a longer development history, this could be a problem.

Likewise, fancy_figure.png and clever_analysis.py are the same for the

first two commits, and then again when you reverted to that copy in

snapshot_6 (that is now commit 9920fff7b55370a2c4c7566011de8aa2a263171f).

You can show these files are the same by checking their hash strings. If

their hash strings are different, the files must be different. All copies of

expensive_data.csv have the same hash, and are therefore identical:

$ shasum */expensive_data.csv

bf2c7158afc60b244cba860fb0b2c04bb6481daf 00d03e9d1bf4ebaea380da3c62e9226189e39ff4/expensive_data.csv

bf2c7158afc60b244cba860fb0b2c04bb6481daf 905376d349af193c367217712bc231186f17fca7/expensive_data.csv

bf2c7158afc60b244cba860fb0b2c04bb6481daf 9920fff7b55370a2c4c7566011de8aa2a263171f/expensive_data.csv

bf2c7158afc60b244cba860fb0b2c04bb6481daf 99b52473039acea4427e13e42b96c78776e2baf5/expensive_data.csv

bf2c7158afc60b244cba860fb0b2c04bb6481daf 9bf4cdd8847feeb49fe94cb96298acf7986a587d/expensive_data.csv

bf2c7158afc60b244cba860fb0b2c04bb6481daf bd9dc5fb9aacf208536fad1fad22696c9a79e277/expensive_data.csv

bf2c7158afc60b244cba860fb0b2c04bb6481daf bee09a3b1c11456c6e1bc6784319954f40fef24b/expensive_data.csv

bf2c7158afc60b244cba860fb0b2c04bb6481daf c203516a49d48389826b041f4d7bd2d39bdf4a57/expensive_data.csv

bf2c7158afc60b244cba860fb0b2c04bb6481daf d9accd0a27c78b4333d70ee1a9d7dca0bcc3e682/expensive_data.csv

bf2c7158afc60b244cba860fb0b2c04bb6481daf staging/expensive_data.csv

bf2c7158afc60b244cba860fb0b2c04bb6481daf working/expensive_data.csv

fancy_figure.png is the same for the first two commits, changes for the

third commit, and reverts back to the same contents at the 6th commit:

$ # First commit

$ shasum 99b52473039acea4427e13e42b96c78776e2baf5/fancy_figure.png

e8fe49b1faf23b428865d0315c4763c6ec459897 99b52473039acea4427e13e42b96c78776e2baf5/fancy_figure.png

$ # Second commit

$ shasum 9bf4cdd8847feeb49fe94cb96298acf7986a587d/fancy_figure.png

e8fe49b1faf23b428865d0315c4763c6ec459897 9bf4cdd8847feeb49fe94cb96298acf7986a587d/fancy_figure.png

$ # Third commit

$ shasum d9accd0a27c78b4333d70ee1a9d7dca0bcc3e682/fancy_figure.png

863cf24c03c6ab1eb33c1022d6fc8f7a2876875a d9accd0a27c78b4333d70ee1a9d7dca0bcc3e682/fancy_figure.png

$ # Sixth commit

$ shasum 9920fff7b55370a2c4c7566011de8aa2a263171f/fancy_figure.png

e8fe49b1faf23b428865d0315c4763c6ec459897 9920fff7b55370a2c4c7566011de8aa2a263171f/fancy_figure.png

You wonder if there is a way to store each unique version of the file just once, and make the commits point to the matching version.

First you make a new directory to store files generated from your commits:

$ mkdir repo

Next you make a sub-directory to store the unique copies of the files in commits:

$ mkdir repo/objects

You play with the idea of calling these unique versions something like

repo/objects/fancy_figure.png.v1, repo/objects/fancy_figure.png.v2 and

so on. You would then need something like a text file called

directory_listing.txt in the first commit directory to say that the file

fancy_figure.png for this commit is available at

repo/objects/fancy_figure.png.v1. This could be something like:

# directory_listing.txt in first commit

fancy_figure.png -> repo/objects/fancy_figure.png.v1

directory_listing.txt for the second commit would point to the same file,

but the third commit would have something like:

# directory_listing.txt in third commit

fancy_figure.png -> repo/objects/fancy_figure.png.v2

You quickly realize this is going to get messy when you are working with other

people, because you may store repo/objects/fancy_figure.png.v3 while

Josephine is also working on the figure, and is storing her own

repo/objects/fancy_figure.png.v3. You need a unique file name for each

version of the file.

Now you have your second quite brilliant hashing idea. Why not use the hash of the file to make a unique file name?

For example, here are the hash values for the files in the first commit:

$ shasum 99b52473039acea4427e13e42b96c78776e2baf5/*

c25a0bd91a7e8eb574b17296a25111233eac94b5 99b52473039acea4427e13e42b96c78776e2baf5/clever_analysis.py

bf2c7158afc60b244cba860fb0b2c04bb6481daf 99b52473039acea4427e13e42b96c78776e2baf5/expensive_data.csv

e8fe49b1faf23b428865d0315c4763c6ec459897 99b52473039acea4427e13e42b96c78776e2baf5/fancy_figure.png

99b52473039acea4427e13e42b96c78776e2baf5 99b52473039acea4427e13e42b96c78776e2baf5/message.txt

To store the unique copies, you copy each file in the first commit to

repo/objects with a unique file name. The file name is the hash of the

file contents. For example, the hash for fancy_figure.png is

e8fe49b1faf23b428865d0315c4763c6ec459897. So, you do:

$ cp 99b52473039acea4427e13e42b96c78776e2baf5/fancy_figure.png repo/objects/e8fe49b1faf23b428865d0315c4763c6ec459897

The hash values for clever_analysis.py and expensive_data.csv are

c25a0bd91a7e8eb574b17296a25111233eac94b5 and bf2c7158afc60b244cba860fb0b2c04bb6481daf respectively, so:

$ cp 99b52473039acea4427e13e42b96c78776e2baf5/clever_analysis.py repo/objects/c25a0bd91a7e8eb574b17296a25111233eac94b5

$ cp 99b52473039acea4427e13e42b96c78776e2baf5/expensive_data.csv repo/objects/bf2c7158afc60b244cba860fb0b2c04bb6481daf

These hash values become the directory_listing.txt for the first commit:

$ cat 99b52473039acea4427e13e42b96c78776e2baf5/directory_listing.txt

c25a0bd91a7e8eb574b17296a25111233eac94b5 clever_analysis.py

bf2c7158afc60b244cba860fb0b2c04bb6481daf expensive_data.csv

e8fe49b1faf23b428865d0315c4763c6ec459897 fancy_figure.png

Finally, you can delete fancy_figure.png, clever_analysis.py and

expensive_data.csv in the first commit directory, because you have them

backed up in repo/objects.

So far you haven’t gained anything much except some odd-looking filenames. The payoff comes when you apply the same procedure to the second commit. Here are the hashes for the files in the second commit:

$ shasum 9bf4cdd8847feeb49fe94cb96298acf7986a587d/*

c25a0bd91a7e8eb574b17296a25111233eac94b5 9bf4cdd8847feeb49fe94cb96298acf7986a587d/clever_analysis.py

bf2c7158afc60b244cba860fb0b2c04bb6481daf 9bf4cdd8847feeb49fe94cb96298acf7986a587d/expensive_data.csv

e8fe49b1faf23b428865d0315c4763c6ec459897 9bf4cdd8847feeb49fe94cb96298acf7986a587d/fancy_figure.png

9bf4cdd8847feeb49fe94cb96298acf7986a587d 9bf4cdd8847feeb49fe94cb96298acf7986a587d/message.txt

47eef829586738a0855060dc83f8e0781fbcac2c 9bf4cdd8847feeb49fe94cb96298acf7986a587d/nobel_prize.md

Remember that, in the second commit, all you did was add the first draft of

the paper as nobel_prize.md. So, all the other files in the second commit

(apart from message.txt that you are not storing) are the same as for the

first commit, and therefore have the same hash. You already have these files

backed up in repo/objects so all you need to do is point

directory_listing.txt at the original copies in repo/objects.

For example, the hash for fancy_figure.png in the second commit is

e8fe49b1faf23b428865d0315c4763c6ec459897. When you are storing the files for the second commit

in repo/objects, you notice that you already have a file

named e8fe49b1faf23b428865d0315c4763c6ec459897 in repo/objects, so you do not copy it a

second time. By checking the hashes for each file in the commit, you find

that the only file you are missing is the new file nobel_prize.md. This

has hash 47eef829586738a0855060dc83f8e0781fbcac2c, so you do a single copy to repo/objects:

$ # Only one copy needed to store files in second commit

$ cp 9bf4cdd8847feeb49fe94cb96298acf7986a587d/nobel_prize.md repo/objects/47eef829586738a0855060dc83f8e0781fbcac2c

As before, you can make directory_listing.txt for the second commit by

recording the hashes of the files:

$ cat 9bf4cdd8847feeb49fe94cb96298acf7986a587d/directory_listing.txt

c25a0bd91a7e8eb574b17296a25111233eac94b5 clever_analysis.py

bf2c7158afc60b244cba860fb0b2c04bb6481daf expensive_data.csv

e8fe49b1faf23b428865d0315c4763c6ec459897 fancy_figure.png

47eef829586738a0855060dc83f8e0781fbcac2c nobel_prize.md

Before you start this procedure of moving the unique copies into

repo/objects, your whole nobel_prize directory is size:

$ # Size of the contents of nobel_prize before moving to repo/objects

$ du -hs .

5.4M .

When you run the procedure above on every commit, moving files to

repo/objects, you have this:

nobel_prize

├── working

│ (5 files)

├── staging

│ (5 files)

├── repo

│ └── objects

│ ├── 18e92be4df9036826fc983c42e2e4fb5c6fed1cb [692B]

│ ├── 27e85e8f524a26a3a77f1c7ea631d6b2ad2b018a [251K]

│ ├── 47eef829586738a0855060dc83f8e0781fbcac2c [730B]

│ ├── 4e3c43a5c0d530fa0ba4305b3c52a9f7a4cb9140 [244B]

│ ├── 5840cded1e61d0a22c0e9f7d62de8c43ff47a402 [716B]

│ ├── 71892a8d170f113b778a9458cd6930abb387328f [238B]

│ ├── 80bf412d6273626674658862caebb131c2df8ddc [979B]

│ ├── 815bbcf64edacb6791cc2ebdc3afeb09797c9347 [181B]

│ ├── 863cf24c03c6ab1eb33c1022d6fc8f7a2876875a [239K]

│ ├── bf2c7158afc60b244cba860fb0b2c04bb6481daf [244K]

│ ├── c25a0bd91a7e8eb574b17296a25111233eac94b5 [618B]

│ ├── e8fe49b1faf23b428865d0315c4763c6ec459897 [183K]

│ ├── efb5308cc0f74a2515ce668adf237b28527fd2bc [279K]

│ └── f2e5e8c8122533fbc1da0684abe7e43471fe1674 [752B]

├── bd9dc5fb9aacf208536fad1fad22696c9a79e277 "Merged Josephine's changes"

│ ├── directory_listing.txt [290B]

│ └── message.txt [173B]

├── 905376d349af193c367217712bc231186f17fca7 "Expand the introduction"

│ ├── directory_listing.txt [290B]

│ └── message.txt [130B]

├── bee09a3b1c11456c6e1bc6784319954f40fef24b "More fun with fudge"

│ ├── directory_listing.txt [290B]

│ └── message.txt [125B]

├── 9920fff7b55370a2c4c7566011de8aa2a263171f "Revert to original script & figure"

│ ├── directory_listing.txt [290B]

│ └── message.txt [140B]

├── c203516a49d48389826b041f4d7bd2d39bdf4a57 "Add references"

│ ├── directory_listing.txt [290B]

│ └── message.txt [120B]

├── 00d03e9d1bf4ebaea380da3c62e9226189e39ff4 "Change parameters of analysis"

│ ├── directory_listing.txt [234B]

│ └── message.txt [135B]

├── d9accd0a27c78b4333d70ee1a9d7dca0bcc3e682 "Add another fudge factor"

│ ├── directory_listing.txt [234B]

│ └── message.txt [130B]

├── 9bf4cdd8847feeb49fe94cb96298acf7986a587d "Add first draft of paper"

│ ├── directory_listing.txt [297B]

│ └── message.txt [130B]

└── 99b52473039acea4427e13e42b96c78776e2baf5 "First backup of my amazing idea"

├── directory_listing.txt [241B]

└── message.txt [87B]

The whole nobel_prize directory is now smaller because you have no

duplicated files:

$ # Size of the contents of nobel_prize after moving to repo/objects

$ du -hs .

2.3M .

The advantage in size gets larger as your system grows, and you have more duplicated files.

Gitwards 10: making the commits unique¶

Up in Gitwards 7: naming commits from hashes you used the hash of message.txt as a

nearly unique directory name for the commit. Your thinking was that it was

very unlikely that any two commits would have the same author, date, time, and

note. You have since added the Parents field to message.txt to make

it even more unlikely. But – it could still happen. You might be careless

and make another commit very quickly after the previous, and without a note.

You could even point back to the same parent.

You would like to be even more confident that the commit message is unique to the commit, including the contents of the files in the commit.

You now have a way of doing this. The directory_listing.txt files

contain a list of hashes and corresponding file names for this commit

(snapshot). For example, here is directory_listing.txt for the first

commit:

$ cat 99b52473039acea4427e13e42b96c78776e2baf5/directory_listing.txt

c25a0bd91a7e8eb574b17296a25111233eac94b5 clever_analysis.py

815bbcf64edacb6791cc2ebdc3afeb09797c9347 directory_listing.txt

bf2c7158afc60b244cba860fb0b2c04bb6481daf expensive_data.csv

e8fe49b1faf23b428865d0315c4763c6ec459897 fancy_figure.png

The contents of this file are (very nearly) unique to the contents of the

files in the snapshot. If any of the files changed, then the hash of the file

would change and the corresponding line in directory_listing.txt would

change. If you renamed the file, the name of the file would change and the

corresponding line in directory_listing.txt would change.

Now you know what to do. You take a hash of the directory_listing.txt

file:

$ shasum 99b52473039acea4427e13e42b96c78776e2baf5/directory_listing.txt

85d49d8555aeb254d1d4acd377034772944a35fe 99b52473039acea4427e13e42b96c78776e2baf5/directory_listing.txt

You put this has into a new field in message.txt called Directory

hash::

Date: April 1 2012, 14.30

Author: I. M. Awesome

Notes: First backup of my amazing idea

Directory hash: 85d49d8555aeb254d1d4acd377034772944a35fe

Now, if any file in the commit changes, directory_listing.txt will change,

and so its hash will change, and so message.txt will change.

Now you’ve added the Directory hash field to messsage.txt you have

also changed the hash values of the message.txt files. Because you’ve

changed the hashes of the message.txt files, you go back through your

commits updating the parent hashes to the new ones, and renaming the commit

directories with the new hashes. You end up with this:

nobel_prize

├── working

│ (5 files)

├── staging

│ (5 files)

├── repo

│ (1 directory)

├── f46773cff294d07a331a6aa0ee32b3615cb009b8 "Merged Josephine's changes"

│ (2 files)

├── 505228057403295fdc16888bed49515a7c1d80a1 "Expand the introduction"

│ (2 files)

├── 5bdbf9b8ac9e998a95495e2d7ae370242c267c52 "More fun with fudge"

│ (2 files)

├── 41234bea0657aecaa234cee2b146051f90062078 "Revert to original script & figure"

│ (2 files)

├── c1072adf649f3ec439e6925af01251b9ccd91410 "Add references"

│ (2 files)

├── 917fb4cfe6c5d13bd4efbac1b54b26ae2967c839 "Change parameters of analysis"

│ (2 files)

├── 2eb0b1ea04d70129e4a4e219e8d51e10effdb8fe "Add another fudge factor"

│ (2 files)

├── 117e7de8e27a54104f7a08d0f75b9ca214eaccb3 "Add first draft of paper"

│ (2 files)

└── 9c0b782981cc2ee322ec4b595dc472799f8808bd "First backup of my amazing idea"

(2 files)

With your new system, if any two commits have the same message.txt then

they also have the same date, author, note, parents and file contents. They

are therefore exactly the same commit.

Note

The commit message is unique to the contents of the files in the snapshot (because of the directory hash) and unique to its previous history (because of the parent hash(es)).

Gitwards 11: away with the snapshot directories¶

You are reflecting on your idea about hashing the directory listing, and your

eye falls idly on the current directory tree of nobel_prize:

nobel_prize

├── working

│ (5 files)

├── staging

│ (5 files)

├── repo

│ └── objects

│ (14 files)

├── f46773cff294d07a331a6aa0ee32b3615cb009b8 "Merged Josephine's changes"

│ ├── directory_listing.txt [290B]

│ └── message.txt [230B]

├── 505228057403295fdc16888bed49515a7c1d80a1 "Expand the introduction"

│ ├── directory_listing.txt [290B]

│ └── message.txt [187B]

├── 5bdbf9b8ac9e998a95495e2d7ae370242c267c52 "More fun with fudge"

│ ├── directory_listing.txt [290B]

│ └── message.txt [182B]

├── 41234bea0657aecaa234cee2b146051f90062078 "Revert to original script & figure"

│ ├── directory_listing.txt [290B]

│ └── message.txt [197B]

├── c1072adf649f3ec439e6925af01251b9ccd91410 "Add references"

│ ├── directory_listing.txt [290B]

│ └── message.txt [177B]

├── 917fb4cfe6c5d13bd4efbac1b54b26ae2967c839 "Change parameters of analysis"

│ ├── directory_listing.txt [234B]

│ └── message.txt [192B]

├── 2eb0b1ea04d70129e4a4e219e8d51e10effdb8fe "Add another fudge factor"

│ ├── directory_listing.txt [234B]

│ └── message.txt [187B]

├── 117e7de8e27a54104f7a08d0f75b9ca214eaccb3 "Add first draft of paper"

│ ├── directory_listing.txt [297B]

│ └── message.txt [187B]

└── 9c0b782981cc2ee322ec4b595dc472799f8808bd "First backup of my amazing idea"

├── directory_listing.txt [241B]

└── message.txt [144B]

It occurs to you that you can move the directory_listing.txt and

message.txt files into your repo/objects directory. When you have

done that, you can get rid of the commit directories entirely.

First you take the hash of each directory_listing.txt and move it into the

repo/objects directory as you did for the other files:

$ shasum 9c0b782981cc2ee322ec4b595dc472799f8808bd/directory_listing.txt

85d49d8555aeb254d1d4acd377034772944a35fe 9c0b782981cc2ee322ec4b595dc472799f8808bd/directory_listing.txt

$ cp 9c0b782981cc2ee322ec4b595dc472799f8808bd/directory_listing.txt repo/objects/85d49d8555aeb254d1d4acd377034772944a35fe

Then you do the same for the message.txt file:

$ cp 9c0b782981cc2ee322ec4b595dc472799f8808bd/message.txt repo/objects/9c0b782981cc2ee322ec4b595dc472799f8808bd

There are 9 commits, so there are 9 x 2 new files with

hash filenames in repo/objects (a hashed copy of directory_listing.txt

and message.txt for each commit).

Now you don’t need the snapshot directories at all, because the hashed files

in repo/objects have all the information about the snapshots.

nobel_prize

├── working

│ (5 files)

├── staging

│ (5 files)

└── repo

└── objects

(32 files)

Note

In git as in your SAP content management system, a repository

directory stores all the data from the snapshots. In your case that

directory is repo. For git, it will be a directory called .git.

Gitwards 12: where am I?¶

You have one last problem to face – where is your latest commit?

When your snapshot directory names had numbers, like snapshot_8, you could

use the numbers to find the most recent commit. Now all you have is a

directory called repo/objects with unhelpful file names made from hashes.

Which of these files has your latest commit?

You could write down the latest commit hash on a piece of paper, after you make the commit, but this sounds like a job better done by a computer.

So, when you make a new commit, you store the hash for that commit in a file

called repo/my_bookmark. It is a text file with the hash string as

contents. Your last commit was f46773cff294d07a331a6aa0ee32b3615cb009b8, so

repo/my_bookmark has contents:

$ cat repo/my_bookmark

f46773cff294d07a331a6aa0ee32b3615cb009b8

You can imagine that, when Josephine is working on the same set of files, she

might want her own bookmark, maybe in a file called josephines-bookmark.

Note

You keep track of the latest commit in a particular sequence by storing the latest commit hash in a bookmark file. In git this bookmark is called a branch.

You are on the on-ramp¶

You now know all the main ideas in git. Follow me then to Curious git to see these ideas come to life in your actual git.